The Guardian’s recent celebration of Jacinda Ardern’s “kindness” reflects the liberal media’s obsession with style over substance, emotional affect over material analysis. Ardern’s global image as a compassionate leader—a sort of progressive antithesis to Trumpism—has become hegemonic in international discourse. She has been lauded for her empathy during the Christchurch mosque attacks, her cautious stewardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, and her symbolic rhetoric of kindness. But behind the soft-lit halo lies a legacy of state violence, capitalist realism, and symbolic politics that maintained the very structures of oppression she was praised for challenging.

Ardern’s leadership has often been described as emotionally intelligent, compassionate, and people-centred. But compassion is not liberation. Empathy alone does not redistribute wealth, dismantle police power, or decommodify housing. What Ardern perfected was a mode of governance that couched neoliberalism in progressive language. A style of leadership that appeared anti-fascist, anti-racist, and feminist, while presiding over deepening inequality, mass incarceration of Māori, ongoing colonisation, environmental destruction, and a housing system that serves landlords and property speculators.

Ardern’s “politics of kindness” masked a status quo commitment to capitalism and state power. Her government’s housing policies floundered under the weight of market logic. Despite the crisis of homelessness and unaffordability, the Labour government never seriously considered nationalising housing, implementing rent controls, or seizing vacant properties from land-bankers. Instead, they protected the interests of property investors, many of whom were MPs themselves.

Under Ardern, the state continued to subsidise agribusiness and fossil fuel extraction while making rhetorical commitments to climate action. The declaration of a climate emergency was not matched by transformative policy. Oil and gas exploration permits continued. Intensive dairy farming—the largest source of emissions—was largely left untouched. Environmentalism became a branding exercise, not a site of struggle against capital.

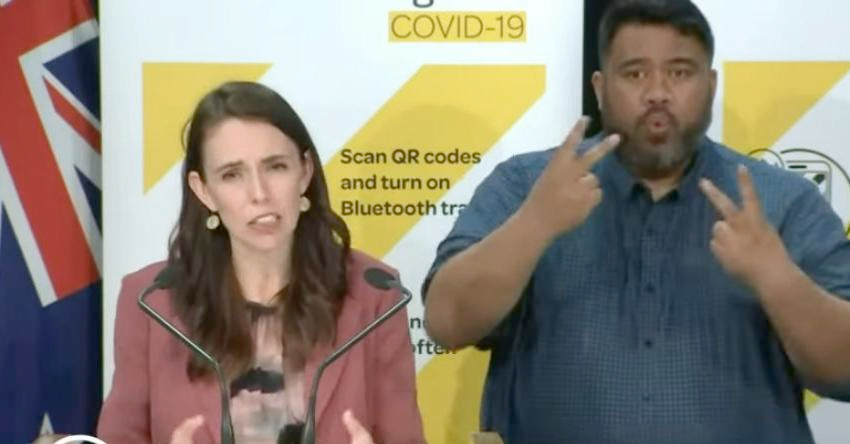

The pandemic further revealed the contradictions of Ardern’s liberal authoritarianism. While early lockdowns saved lives and were publicly supported, they also concentrated state power and discipline. The response relied heavily on individual responsibility and police enforcement, disproportionately targeting poor and marginalised communities. Meanwhile, billionaires like Graeme Hart saw their wealth surge, and landlords continued to extract rent while workers were laid off.

Rather than seizing the opportunity to radically restructure the economy, through wealth taxes, universal public housing, or nationalising essential services, Ardern’s government opted for Keynesian stimulus that ultimately stabilised capital. The “team of five million” rhetoric flattened class distinctions, erasing the reality that some could isolate in spacious homes while others worked in frontline, precarious jobs.

The danger of the Ardern mythos lies not in her personal qualities, but in the broader ideological function she serves. Her leadership rehabilitated the legitimacy of the capitalist state by humanising it. She proved that you don’t need to be a brute like Trump or a technocrat like Macron to govern effectively under capitalism – you can smile, wear a hijab, and cry on television while maintaining prisons, protecting landlords, and pacifying the poor.

This is the liberal fantasy: that the system can be made kind. That capitalism can be managed with empathy. That colonisation can be reconciled. But from an anarcho-communist perspective, the state, no matter how kind it pretends to be, is still an instrument of domination. Ardern’s charm only made the pill easier to swallow.

Jacinda Ardern’s resignation was met with eulogies for a politics of empathy and civility. But civility is not justice, and symbolism is not revolution. Her tenure exposes the limits of progressive statecraft—it can temporarily soothe, but it cannot emancipate.

What is needed is not kinder prime ministers, but the abolition of the prime ministership. Not empathy from above, but solidarity from below. Anarcho-communism calls for a complete rupture with the capitalist nation-state, and the creation of a decentralised, non-hierarchical society based on mutual aid, workers’ control, and Indigenous sovereignty.

True liberation will not come from Parliament – it will come from the streets, the picket lines, the papakāinga, and the barricades.